In 2012 a Swedish report drew attention to an impressive increase in the relative citation impact of Danish research, which was so exceptional that it was referred to as a «Danish miracle». In a recent follow-up report we find that the relative citation impact for publications affiliated to Denmark has seen a continuous decline since 2010.

Jesper Wiborg Schneider, Professor, Aarhus University

Maria-Theresa Norn, Senior Researcher, Aarhus University, and Associate Professor, Technical University of Denmark

In 2012, Gunnar Öquist and Mats Benner published a report that sought to explain why the relative impact of Swedish research declined, while the relative impact of research from countries like Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland had increased.

Their report gained substantial attention in Denmark because it drew attention to the unusual development in Danish research impact in the period 1990–2010. Drawing on findings from a bibliometric study covering 39 countries (Karlsson and Persson 2012), it showed an impressive increase in mean citation impact and in the proportion of highly cited papers over the two decades.

This development was particularly remarkable in light of the marked decrease in relative impact of Danish research in the 1980s. The impact had deteriorated so much that a 1990 report warned against an “impending catastrophe” for the Danish research system (Nørretranders and Haaland 1990). Yet rather than end in “catastrophe”, Danish research entered two decades of growing research impact.

The Danish Miracle

The development in Danish research impact from 1990 to 2010 was seen as so exceptional, that Öquist and Benner (2012) referred to it as a “Danish miracle” (p. 39). They argued that research policy initiatives in Denmark – for instance increased research resources, reforms of doctoral educations, the university sector and the research funding system – and a “culture of academic excellence” (p. 36) had contributed to this development.

Not surprisingly, these conclusions were warmly received by the Danish research system and policymakers. Attempts to explain the “Danish miracle” generally echoed Öquist and Benner’s (2012) argument that it was the result of a fortuitous combination of many historical developments in research and research funding rather than of a carefully designed political masterplan to strengthen Danish research (Aagaard and Schneider 2014; DFiR 2016).

At the beginning of the 2010s, indications that Danish research impact was stagnating (Aagaard and Schneider 2014) gave rise to concerns about the long-term health of the Danish research system (DEA 2014). So how has the relative citation impact of Danish research developed in the last decade? In a recently published study, we updated and extended the bibliometric analyses presented in Öquist and Benner’s report (Karlsson and Persson 2012) to examine the development since 2009 in the relative citation impact for publications affiliated to Denmark (Schneider & Norn, 2023).

Declining relative research impact – in Denmark, but also in comparable countries

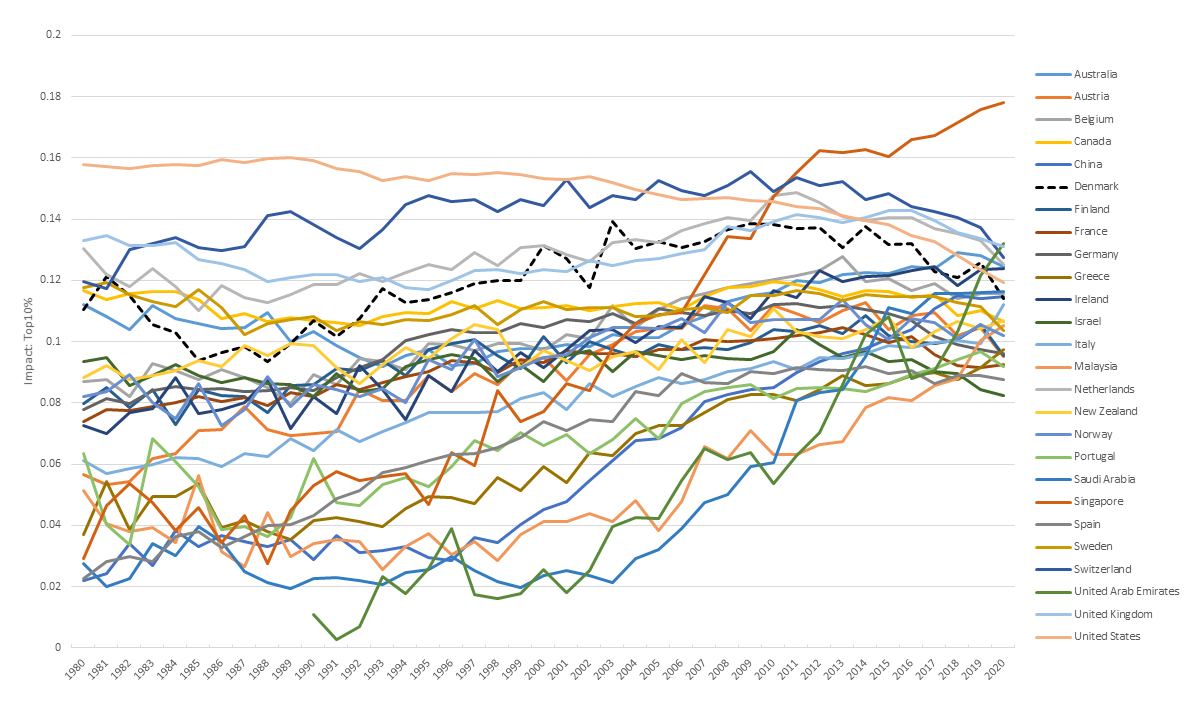

Our study documents a continuous decline since 2010 in the relative citation impact for publications affiliated to Denmark. Similar declines are observed in several other countries with which Denmark is often compared, but the Danish decline sets in earlier and appears more pronounced. Whereas Denmark around 2010 belonged to a small group of countries with the highest relative citation impact, today, Denmark belongs to a much larger group of countries with a lower albeit above-average citation impact.

The decline appears across major scientific fields and universities, with minor variations and a few exceptions. For instance, it appears more pronounced in scientific fields that are typically considered strongholds in Danish research. It is more pronounced among the three largest universities.

We also document that the Danish research system has grown significantly over the past decade, and more than in other countries. Full-count publications have increased fivefold, and fractional-count publications more than threefold since 1990. The number of publishing researchers has increased by 60 per cent from 2009-11 to 2018-20.

The system has expanded in size due to the increasing number of PhD students and postdocs trained at Danish research institutions and a substantial increase in external funding. As such, the nature and aims of the research system are continuously evolving, which may affect how we assess its relative impact.

It is also worth noting that – of the countries examined in our study – Denmark has seen the least renewal in the group of researchers that produce highly cited articles from the period 2009-11 to 2018-20. Put differently, the people who were central in driving research impact ten years ago are more likely to drive impact today as well for Denmark than for other countries.

Cause for concern?

The developments in citation impact may be surprising. As mentioned, the relative impact of Danish research is now at the same level as in the early 1990s. Yet we know from prior studies that small nations can have significantly better or worse citation impact than large nations whose performance is more directly tied to overall international developments in citation impact. Given the exceptional relative citation impact of Danish research in 2010, and given that we in the 2010s began to see the effects of substantial additional investments in Danish research starting in the 2000s, driven by the Globalization Fund (2007–2012) and by the marked increase in private philanthropic research funding, expectations to Danish research performance in 2020 were high.

At the very least, it no longer makes sense to speak of a “Danish miracle”. From being in an exclusive group of the most cited research nations in the world, Denmark is today positioned in a larger group of countries with seemingly converging impact levels. Denmark’s impact level is still at the higher end of this group, but it is declining, whereas several other countries’ levels have increased (see Figure 1).

The system is converging

Our study reveals that the overall system, at the country level, appears to be converging: the differences in relative citation impact of countries are becoming smaller. This is no doubt a consequence of substantial international research collaboration.

Moreover, almost every second paper in the database now has co-authors from the US and/or China, underlining the growth in volume of research from China over the past decade. When the US and China engage internationally, they most frequently collaborate with each other. Their citation patterns are distinct from those of other countries in that around 50 per cent of their citations are national self-citations. Consequently, given their size and idiosyncrasies, US and China to some unknown extent influence the developments in the short-term citing patterns in the citation databases (we use Web of Science).

It is tempting to conclude that the results show that Danish research quality has gradually deteriorated since 2010. But this is wrong. While it may be discussed how accurately citation impact measures “research quality” (Aksnes, Langfeldt & Wouters, 2019), there is no doubt that it is still by many perceived as one of the better indicators of quality”.

What impact truly measures

The narrative around the “Danish miracle” clearly saw citation impact as a confirmation of general perceptions of high performance and strong quality in the Danish research system. But citations are a noisy way to measure the use of literature.

What impact can reveal is patterns of visibility, which is an interesting indicator as it provides information on contributions to, and dynamics in, research fronts. Impact is therefore primarily depicting dynamic social structures – with all their path dependencies and inherent biases. So high citation impact at the country level may very well imply strong research, that is, research which is visible and used. A decline in Danish relative citation impact therefore indicates a change in the role of Danish research publications in the global research system and its research fronts.

The matter is complicated further by the fact that many publications are shared among countries. We often use fractional counting to divide credits among countries, and impact therefore becomes not only relative; it also plays out as an annual zero-sum game measured in a complex, dynamic and evolving database. When some countries grow in their relative impact, others will yield. And the database used as the basis for the bibliometric analyses reported here has indeed grown substantially during the period of study.

The remarkable growth of China has no doubt influenced publication and citing patterns to an extent that some of the previously highest performing countries are experiencing a decline effect. But it is noticeable that the whole system seems to be converging (with a few exceptions), indicating that measuring science systems based on international journal citation databases raises questions about “national” research and the ways in which we count it.

However, changes in the database or the overall system only explain part of the decline in the relative research impact of publications with Danish affiliations. Other countries are doing better. The UK, Sweden and Norway have seen smaller declines in their relative research impact than Denmark, and Ireland, Australia, Belgium, Greece and Slovenia have managed to increase their relative impact during the period where Denmark and other countries have seen a decline.

The decline in the relative impact of Danish research that we document is certainly not cause for great alarm, but it may be cause for concern – a signal of subtle changes in the conditions for knowledge production and the long-term impact of Danish research.

The aim of our study was not to speculate on possible explanations of the change in relative Danish research impact but merely to take stock a decade after Öquist and Benner’s (2012) report. We hope that our study will contribute to an informed debate on the current state and future prospects of Danish research – and spur further work to better understand the performance of research from Denmark as well as the factors that shape this performance.

The study referenced in this article was undertaken by researchers at the Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy (CFA) at the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University. The study was commissioned and funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the VILLUM FOUNDATION. The full report, “The scientific impact of Danish research 1980-2020”, can be accessed via this link: https://cfa-research.au.dk/publications/2023/3/1

Mats Benner comments on the recent developments in Denmark in «You were human after all» (Danmark har blivit en land bland andra)

References

Aagaard, K. and Schneider, J.W. 2014. Hænger forskningspolitik og international succes sammen? Altinget. 2. april. https://www.altinget.dk/forskning/artikel/hvordan-haenger-forskningspolitik-og-international-succes-sammen

Aksnes, D. W., Langfeldt, L., & Wouters, P. (2019). Citations, Citation Indicators, and Research Quality: An Overview of Basic Concepts and Theories. SAGE Open, 9(1), doi:10.1177/2158244019829575

DEA. 2014. Dansk forskning anno 2030: Er vi stadig i verdensklasse? Debatoplæg fra Tænketanken DEA. https://dea.nu/i-farver/publikationer/debatoplaeg-dansk-forskning-anno-2030-er-vi-stadig-i-verdensklasse

DFiR. 2016. Viden i verdensklasse. Rapport fra Danmarks Forsknings- og Innovationspolitiske Råd (DFIR). https://ufm.dk/publikationer/2016/viden-i-verdensklasse/viden-i-verdensklasse-hvorfor-klarer-dansk-forskning-sig-sa-godt

Karlsson, S. and O. Persson. 2012. The Swedish Production of Highly Cited Papers. 5. Vetenskapsrådets Lilla Rapportserie. Vetenskapsrådet [The Swedish Research Council].

Nørretranders, T. and T. Haaland. 1990. Dansk dynamit: Dansk forsknings internationale status vurderet ud fra bibliometriske indikatorer [Danish Dynamite: The International Status of Danish Scientific Research, Based on Bibliometric Indicators].” Forskningspolitik 8. Copenhagen: Forskningspolitisk Råd.

Schneider, J. W. and Norn, M.-T. 2023. The scientific impact of Danish research 1980-2020. Report from the Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy.

https://cfa-research.au.dk/publications/2023/3/1/

Öquist, G. and M. Benner. 2012. Fostering Breakthrough Research. (Akademirapport). The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. http://www.forskasverige.se/wp-content/uploads/Fostering-Breakthrough-Research.pdf

Top photo: University of Odense, campus, photo by Westersoe

This is a longer version of the article published in the print edition of Forskningspolitikk,